One of the most legendary origin stories in comics — an industry fraught with legendary origin stories — is the one about the Silver Surfer. Not the origin story of the Surfer in Marvel Comics’ fictional universe, but rather the origin of the character in the all-too-real world.

Cognoscenti will recall that in the Silver Age (the roughly 15-year period from the mid-1950s until around 1970), Marvel’s output was scripted via what came to be known as “the Marvel Method.” Instead of giving the pencil artist a complete manuscript from which to draw the story, the writer — usually Stan Lee, in those days — would instead provide a more general outline that might range from a few paragraphs (or even a few sentences) to a mere list of plot points. The artist would develop the visual story however he deemed fit. When the pages were completed, the writer would then fill in dialogue and captions that suited whatever the artist had drawn. This often meant that the writer had little clear idea what images would appear on those pages when they came off the artist’s table.

When Lee received from artist and co-creator Jack Kirby the pencil art for Fantastic Four #48, famous today as the first book in the three-issue arc that introduced the cosmic supervillain Galactus, he was surprised to see that Kirby had drawn in a character riding a flying surfboard. Kirby explained that he thought Galactus — a gigantic, supremely powerful humanoid being who consumed planets to ingest their energy — needed a herald, someone who would warn the denizens of worlds in Galactus’s path to prepare for their doom. After some initial reluctance, Lee wrote the character into the story. Later, the Surfer became a major point of contention between Lee and Kirby, who each had radically different ideas about how the Surfer’s persona and back-story should evolve.

As I’ve intimated in previous Comic Art Fridays, I tend to be a Marvel Method scripter when it comes to my commissions. Typically, I give the artist the barest of instruction — no more than the names of the character(s) to be depicted, in most cases — and allow him or her free rein to draw whatever pleases their creative sensibilities. Therefore, I’m always at least a little bit surprised by the finished product. And on occasion, like Jack Kirby and his Silver Surfer, an artist completely startles me by including an element in a drawing that I never expected to see.

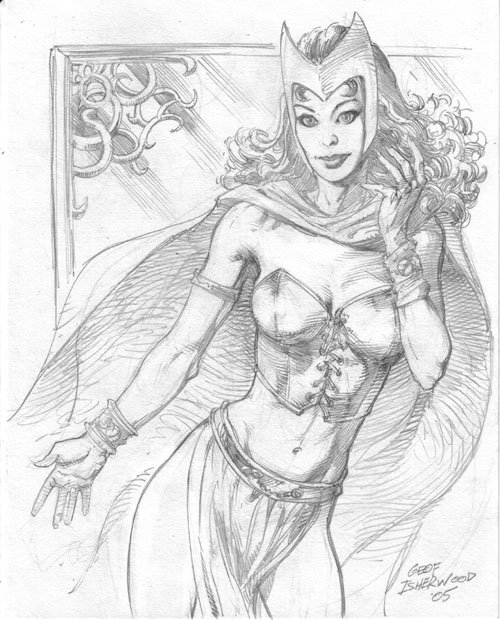

The first artist ever to throw me a happy curveball in this regard was Geof Isherwood. One of my first commissions from Geof was an ink drawing of Valkyrie, a favorite heroine from her days in Marvel’s superteam book, The Defenders. My only direction to Geof involved Val’s weaponry; I wanted him to make use of both her trademark sword (named Dragonfang) and spear (named… um… Spear, I guess). I was totally shocked, then, when Geof sent me a scan of the completed artwork. There alongside Valkyrie, in all his glory, stood her winged stallion Aragorn. (Apparently someone in the ’70s Marvel Bullpen dug The Lord of the Rings.)

As you can see in the image above, Geof’s equine illustration is impeccably detailed and astonishingly accurate. How many comic book artists can draw a horse that well?

When I asked Geof why he’d gone to all that extra (and uncompensated) work, he said simply, “She (Valkyrie) just didn’t seem complete without him (Aragorn).” Of course, he was correct.

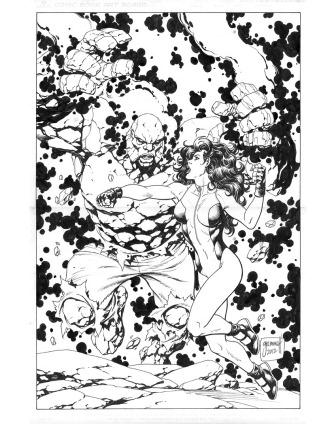

Later that same year, I commissioned an artist named Scott Jones — who frequently signs his work “Shade” — to draw a Common Elements piece featuring Liberty Belle, the Golden Age heroine most closely associated with the All-Star Squadron (and, in her present-day incarnation, the Justice Society of America), and an obscure character from a now-defunct Webcomic, Liberty the American Girl. Once more, I was blown away when I discovered that Scott had included yet another figure in his drawing, none other than the Statue of Liberty herself.

As I had with Isherwood, I asked Scott why he added the additional figure (which, again, is painstakingly accurate and beautifully detailed). His response mirrored Geof’s: “A Liberty-themed scene just wouldn’t have been complete without the Statue of Liberty in there.” And of course, Scott also was correct.

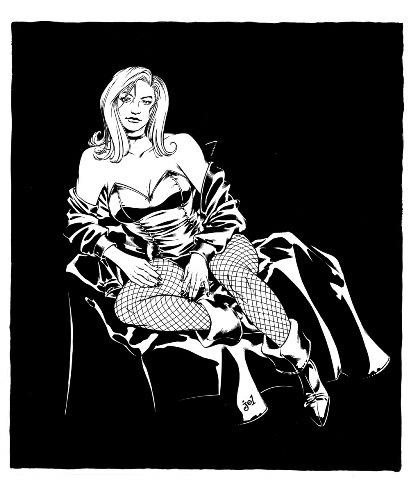

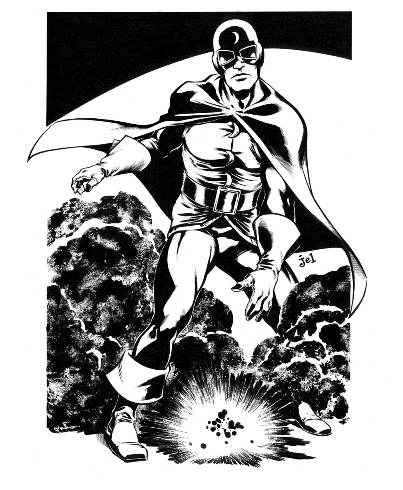

Artists who take on commission projects almost always quote additional fees beyond their typical charges when called upon to add backgrounds or extra characters. And well they should — artists deserve fair compensation for their work, and more work merits more pay. I support that principle wholeheartedly. As someone who routinely commissions multiple characters for my Common Elements themed pieces, and specialized design work for my Bombshells! pinups, I always expect to pay an artist more when I request these items. But I’ve been pleasantly surprised on numerous occasions by artists whom I’ve paid for a simple one- or two-character drawing, who have thrown in a detailed background — or even another character or three — without asking for another dime.

Why do they do it? Because they just can’t let the art their drawing tables until they’re satisfied with the product… and it just needs that extra something.

I hope I always remember to say thanks.

And that’s your Comic Art Friday.

Recent Comments